I am writing this post in order to have a spot where I can find all this info that I have collected over the years in one spot, and not have to retrace my steps all over the place.

The internet is really useful in researching little tidbits of history that one runs into here and there. Memphis has so many stories that most people don't know much about. Hundreds of years ago, long before the Spanish and French explorers, there was a thriving city of the Mound-builders. They had trade routes that extended as far as the South West and into Mexico. DeSoto passed through on his exploration of the Mississippi River, and the French had a trading fort here in the 1700's.

In the early 1800's Andrew Jackson, Isaac Winchester, and John Overton came out from Nashville and laid out the plans for the city of Memphis, to be named for the great Egyptian city on the Nile. The city was established in 1819. After the Civil War the city was one of the fastest growing cities in the nation, and wealthy, too. Memphis had a Mardi Gras tradition second only to New Orleans. One Mardi Gras, the large fountain at Court Square (which still is there) was filled with champaign.

By the 1870's about half the population were newcomers from the country and immigrants from Europe. But a series of yellow fever epidemics in the late 1870's-1880's decimated the population. In the epidemics about half the population died, and of the remaining half, half of them were sick. Hardest hit were the European immigrants, which gave Memphis a long-standing reputation of being unhealthy and a bad place to live. From that point, most of Memphis's growth came from migration from the surrounding rural areas, and the primary story of Memphis became one of black and white.

There are a couple of very interesting stories from the early days of Memphis that were seldom (or ever) mentioned when I was growing up. Only in the past 10 or 15 years have there been any newspaper articles or other write ups of these matters: the story of Frances Wright and Nashoba, and the story of the story of the first mayor of Memphis, and his wife.

The internet is really useful in researching little tidbits of history that one runs into here and there. Memphis has so many stories that most people don't know much about. Hundreds of years ago, long before the Spanish and French explorers, there was a thriving city of the Mound-builders. They had trade routes that extended as far as the South West and into Mexico. DeSoto passed through on his exploration of the Mississippi River, and the French had a trading fort here in the 1700's.

In the early 1800's Andrew Jackson, Isaac Winchester, and John Overton came out from Nashville and laid out the plans for the city of Memphis, to be named for the great Egyptian city on the Nile. The city was established in 1819. After the Civil War the city was one of the fastest growing cities in the nation, and wealthy, too. Memphis had a Mardi Gras tradition second only to New Orleans. One Mardi Gras, the large fountain at Court Square (which still is there) was filled with champaign.

By the 1870's about half the population were newcomers from the country and immigrants from Europe. But a series of yellow fever epidemics in the late 1870's-1880's decimated the population. In the epidemics about half the population died, and of the remaining half, half of them were sick. Hardest hit were the European immigrants, which gave Memphis a long-standing reputation of being unhealthy and a bad place to live. From that point, most of Memphis's growth came from migration from the surrounding rural areas, and the primary story of Memphis became one of black and white.

There are a couple of very interesting stories from the early days of Memphis that were seldom (or ever) mentioned when I was growing up. Only in the past 10 or 15 years have there been any newspaper articles or other write ups of these matters: the story of Frances Wright and Nashoba, and the story of the story of the first mayor of Memphis, and his wife.

This is a picture of Frances Wright (Fanny, as she was known), who founded the intentional community of Nashoba Plantation in what is now Germantown, Tennessee, based on the principles of racial and sexual equality. It lasted from 1825 through about 1830 (longer than the more well known New Harmony Community founded by Robert Owen, which inspired her), when the remaining inhabitants were resettled in the independent Black republic of Haiti. Fanny Wright's grand idea was to eliminate slavery by purchasing slaves, having them learn self supporting skills at Nashoba, working and earning money to finance the purchase of more slaves, freeing them, and repatriating them to Haiti and Liberia. She also advocated full equality of men and women and free universal public education. Fanny was a prolific writer, her works being read and commented on by Thomas Jefferson and later by Walt Whitman. She was a good friend of General Lafayette, accompanying him on his trip to the U.S. to visit Thomas Jefferson. Fanny herself had left Nashoba after falling ill with Malaria.

Now, when I was growing up, although there was a historic marker way north in the county that stated succinctly something about the existence of the "Nashoba Commune, which was a failure", there were no displays of artifacts, no archeological digs (the house itself burned in the 1970's, having been rental property for years and years with no indication or designation as to its history), and no reference to it any school class that I was in. During the past 10 years I have seen a little bit more written about it, as there was an effort to get a historic marker for placement in Germantown (the existing marker is not on the site at all), which was denied by the state of Tennessee supposedly because of the marker in the north part of the county. From the time of Nashoba Plantation, up through my childhood, Fanny Wright was vilified as advocating "free love" and "race mixing".

Now, when I was growing up, although there was a historic marker way north in the county that stated succinctly something about the existence of the "Nashoba Commune, which was a failure", there were no displays of artifacts, no archeological digs (the house itself burned in the 1970's, having been rental property for years and years with no indication or designation as to its history), and no reference to it any school class that I was in. During the past 10 years I have seen a little bit more written about it, as there was an effort to get a historic marker for placement in Germantown (the existing marker is not on the site at all), which was denied by the state of Tennessee supposedly because of the marker in the north part of the county. From the time of Nashoba Plantation, up through my childhood, Fanny Wright was vilified as advocating "free love" and "race mixing".

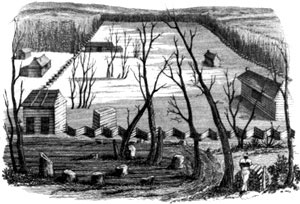

This is a sketch of Nashoba Plantation from Frances Trollope's book "Domestic Manners of the Americans", published in 1832. Tollope was a good friend of Wright's, and visited and stayed with her in Nashoba in 1827 while she was traveling in the United States.

In the research to obtain the elusive historic marker, there was the tantalizing comment that Frances Wright was pretty much ostracized by the Memphis gentry (such as it was), except for the wife of Mayor Winchester, who was her only friend. Marcus Winchester had sold Fanny some of the land that would become Nashoba. I embarked on an internet search to try to find out more about the wife of Marcus Brutus Winchester, Fanny Wright's only friend in Memphis, who would ride out 15 miles in the country to visit. I remembered an article I had read in our local bar association newsletter some years ago that made reference to Marcus Winchester bringing home a wife from New Orleans, who was shunned by Memphis society and I started from there.

Marcus was the son of Isaac Winchester, one of the "founders" of Memphis. Previous to the Memphis land deal with Andrew Jackson and John Overton, Isaac had already been involved in laying out and establishing the city of Cairo, Illinois. Isaac actually named the city Ca Ira -- for the rallying cry of the French Revolution, but it was later morphed into "Cairo". Isaac was not only a supporter of the French Revolution, but he also named his children after populist heroes: the siblings of Marcus Brutus Winchester included Brutus, Selina, Lucilius, Almire, Napoleon, and Valerius Publicola.

Marcus Brutus Winchester took over Isaac's business and real estate interests in the Memphis area and was a wealthy and respected merchant. In 1823 he made a trip down to New Orleans and returned to Memphis with a wife: Marie Louise Amirante Loiselle, sometimes referred to as "Mary". Memphis society was shocked. Not because she was French, but because she was a "woman of color". Interracial marriages had only just been made illegal in Memphis in 1822. It is said that he met Marie Loiselle while on a business trip to St. Louis, where she was the beautiful daughter of a "mullatto" fur trader. She had been educated in France and was well read, fluent in French, and of impeccable deportment. They fell in love and returned by riverboat -- going down to New Orleans for the marriage ceremony. Winchester was elected as the first mayor of Memphis, serving one term from 1827 to 1829, ultimately becoming less popular because of his and his wife's association with Nashoba Plantation and Frances Wright. Frances' sister Camille had a house in town, next door to that of the Winchesters. The Winchesters' house stood about where the Pyramid (soon to be a Bass Pro Shop)now stands in downtown Memphis, overlooking the river.

Marcus served as Post Master for Memphis for many years, but ultimately in 1837 the city of Memphis passed an ordinance prohibiting "the keeping of colored wives within the city limits". The Winchester family then moved to a tract of land outside the city limits known as Muskogee Camp. Marie died two years later in 1839. Marcus and Marie had 8 children: Laura, Robert (named after New Harmony Utopian community founder Robert Dale Owen), Frances (named after Nashoba founder Frances Wright), Louis, Selima, Loiselle, Valeria, and Lisia. The Memphis 1830 census lists the Winchester children as "non-white". By the 1840 census, after Marie's death and after Marcus remarried, the Winchester offspring are listed as "white", and apparently successfully crossed the "color line".

Many descendants of Marcus and Marie Winchester still live in the Memphis area, some quite prominent, including Memphis City Council Member Bill Boyd, and attorney Lee Winchester. I read comments by some descendants that say they were told growing up, that Marie Winchester was Native American, never Black. I remember research being done when I was an Anthropology student and on into Law School, indicating it was statistically unlikely for all of the "white" people claiming Native American heritage in the south in the 1960's-90's to in fact be descended from Native Americans, because the population was just not here. That in fact, in many cases Black heritage was far more likely (given the population numbers) and had probably been euphamized in to Native heritage, which in the south was far more acceptable to the white community in the 60's-90's than black heritage. This is born out by my personal experience as an adoption attorney and dealing with white birth mothers in the 1980's, also noticed and commented on by area adoption social workers, where the white birth mothers of biracial children would allege that the birth father of the child they wanted to place was Hispanic, never African American, despite the fact that the Hispanic population of Memphis in the 1970's, '80's, and 90's was minuscule.

Sources: "Notable Black Memphians", Miriam DeCosta-Willis, 2008; "Memphis in Black and White", Beverly Bord, 2003; "Hellhound on His Tail", Hampton Sides, 2010; Commercial Appeal May 26, 2009; "American Plague", Molly Crosby, 2007; "Marcus and Davy", Memphis Daily News May 13, 2011; Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture; www.memphishistory.net; memphishistory.com; findagrave.com; ancestry.com

In the research to obtain the elusive historic marker, there was the tantalizing comment that Frances Wright was pretty much ostracized by the Memphis gentry (such as it was), except for the wife of Mayor Winchester, who was her only friend. Marcus Winchester had sold Fanny some of the land that would become Nashoba. I embarked on an internet search to try to find out more about the wife of Marcus Brutus Winchester, Fanny Wright's only friend in Memphis, who would ride out 15 miles in the country to visit. I remembered an article I had read in our local bar association newsletter some years ago that made reference to Marcus Winchester bringing home a wife from New Orleans, who was shunned by Memphis society and I started from there.

Marcus was the son of Isaac Winchester, one of the "founders" of Memphis. Previous to the Memphis land deal with Andrew Jackson and John Overton, Isaac had already been involved in laying out and establishing the city of Cairo, Illinois. Isaac actually named the city Ca Ira -- for the rallying cry of the French Revolution, but it was later morphed into "Cairo". Isaac was not only a supporter of the French Revolution, but he also named his children after populist heroes: the siblings of Marcus Brutus Winchester included Brutus, Selina, Lucilius, Almire, Napoleon, and Valerius Publicola.

|

| Marcus Winchester |

Marcus served as Post Master for Memphis for many years, but ultimately in 1837 the city of Memphis passed an ordinance prohibiting "the keeping of colored wives within the city limits". The Winchester family then moved to a tract of land outside the city limits known as Muskogee Camp. Marie died two years later in 1839. Marcus and Marie had 8 children: Laura, Robert (named after New Harmony Utopian community founder Robert Dale Owen), Frances (named after Nashoba founder Frances Wright), Louis, Selima, Loiselle, Valeria, and Lisia. The Memphis 1830 census lists the Winchester children as "non-white". By the 1840 census, after Marie's death and after Marcus remarried, the Winchester offspring are listed as "white", and apparently successfully crossed the "color line".

Many descendants of Marcus and Marie Winchester still live in the Memphis area, some quite prominent, including Memphis City Council Member Bill Boyd, and attorney Lee Winchester. I read comments by some descendants that say they were told growing up, that Marie Winchester was Native American, never Black. I remember research being done when I was an Anthropology student and on into Law School, indicating it was statistically unlikely for all of the "white" people claiming Native American heritage in the south in the 1960's-90's to in fact be descended from Native Americans, because the population was just not here. That in fact, in many cases Black heritage was far more likely (given the population numbers) and had probably been euphamized in to Native heritage, which in the south was far more acceptable to the white community in the 60's-90's than black heritage. This is born out by my personal experience as an adoption attorney and dealing with white birth mothers in the 1980's, also noticed and commented on by area adoption social workers, where the white birth mothers of biracial children would allege that the birth father of the child they wanted to place was Hispanic, never African American, despite the fact that the Hispanic population of Memphis in the 1970's, '80's, and 90's was minuscule.

Sources: "Notable Black Memphians", Miriam DeCosta-Willis, 2008; "Memphis in Black and White", Beverly Bord, 2003; "Hellhound on His Tail", Hampton Sides, 2010; Commercial Appeal May 26, 2009; "American Plague", Molly Crosby, 2007; "Marcus and Davy", Memphis Daily News May 13, 2011; Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture; www.memphishistory.net; memphishistory.com; findagrave.com; ancestry.com

1 comment:

This is very interesting and informative. You have the wrong first name of the person who was the father of Marcus Winchester. His first name was James, He built Cragfont Plantation in Tenn. Marcus is my grandfather 5X back. I did have my DNA done and I do have Native American and African blood in me; although a very small percentage at this point. This is from my mother's side of the family, not my fathers side. I guess what I am saying here is I do believe that Marie had both native american and black heritage. Sincerely, Anita Jessop

'

Post a Comment